Market Pulse: July 8, 2024

Lou Brien is a Strategist/Knowledge Manager at DRW and keeps an eye on the Fed and the economy in general. Find his market insights for the week below.

The Fed talks a lot. The Chair has eight scheduled press conferences every year. The boss and his cohorts also have a wide variety of other types of speaking engagements, such as: Federal Reserve and foreign central bank events, they talk to economic associations, they have breakfast and/or lunch with civic groups, they appear on TV and radio and in the last few years Fed Governors and Fed bank Presidents show up for lively discussions at events that are called “fireside chats”. Back in the day there wasn’t nearly so much central bank chatter as there is today. So, when there was an event at which the Fed Chair, or any other Fed official for that matter, was going to appear it was kind of a big deal. The market was parched for information about how the Fed viewed the state of the economy and therefore how they planned to act in the near and medium term, so Fed speak was seen as the chance to slake their thirst for information about monetary policy. The Fed Chair’s semiannual appearance before the Senate Banking and House Financial Services Committees, the Humphrey/Hawkins Testimony, was the biggest splash, the most anticipated bit of Fed speak on the calendar every year. This was the big opportunity for the market to hear what the Fed was thinking and as a result this testimony set the direction for the markets for several weeks thereafter. The Humphrey/Hawkins was important for the market, but it was also important for the Fed. The Fed Chair was able to pull back the curtain a little bit, and explain what the Fed was thinking about and hint at what was going to happen next. If artfully executed the Fed could convince the market to swim in the same direction as policy, as opposed to working against it. Therefore, the Chairperson’s testimony was usually detailed, occasionally nuanced and often exhaustive. In the days before the Fed got so chatty the Fed Chairs had to take advantage of the important venues. In the current day the Humphrey/Hawkins is just another Tuesday. Back in 1999 the semi-annual testimony presented by Alan Greenspan was more than five thousand words. In March 2024 Jerome Powell read from a text that was less than one thousand words. Three weeks ago, Powell fielded questions from the press for one hour after the FOMC policy meeting. A week ago, Powell participated in an ECB event and answered a few more questions about policy. It’s not likely there will be a surprise at this week’s testimony, but that doesn’t mean we will not learn something new, for instance… It is more than likely that Fed policy is at, or very near, a turning point; a rate cut is a matter of when, not if. The consistent rise in the Unemployment Rate is an ominous sign for the labor market in particular, and the economy in general. The Rate is seven tenths off its cycle low, it is at the highest level since November 2021, and it has increased in each of the last three months. The Unemployment Rate is just one of several bits of labor market data that has softened in the last year or so. The steady rise in Nonfarm Payrolls stands as a contrasting bright spot in a sector that is, by and large, dimming. You would have to look back several decades to find a time when the Fed allowed the jobless rate to run-up so far as they have now, without easing policy with multiple rate cuts. Clearly the Fed’s reluctance to ease in response to the rise in the Unemployment Rate is because inflation, though trending lower, is still too high and the future path down to the target is not yet a sure thing in the mind of the Fed. However, the Fed may be closer than it appears to setting policy based on trouble in the labor market and setting aside any concerns that inflation could rebound. Powell now says the dual mandate is back in balance, the inflation story no longer overshadows the maximum employment imperative, they are equal weighted. The Fed hasn’t acted now, in regards to the jobless rate, as they usually would have in the past because the final mile for inflation has kept them from doing so. But what if there was just one more significant indicator that bolsters confidence about inflation’s near-term path; would that be justification enough to react to the jobless rate increase sooner rather than later?

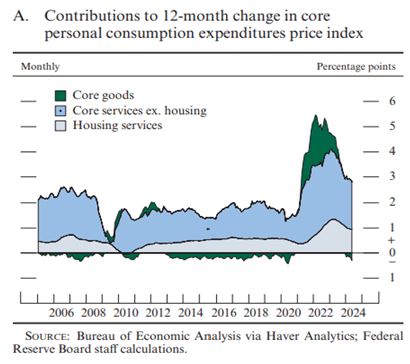

The Fed’s Monetary Policy Report is about eighty pages of data and views on the economy and monetary policy; it is a soup to nuts report. But there is pride of place for some topics, suggesting they are top of mind for the Fed. Some items get special attention; a few economic issues are highlighted in distinct boxed sections. The first boxed item in the latest report, released on July 5, is called “Housing Services Inflation and Market Rent Measures”. The section explains the influence of housing services pricing in the PCE price index.

“The price index for housing services includes rents explicitly paid by renters as well as implicit rents that homeowners would have to pay if they were renting their homes known as owners’ equivalent rent (OER). This index is an important component of the price index for personal consumption expenditures (PCE), composing about 15 .5 percent of the total PCE price index. Housing services prices started accelerating in 2021, and, as figure A illustrates, the contribution of these prices to the 12-month change in the core PCE price index increased notably, reaching a peak of 1 .4 percentage points in 2023. In May 2024, the contribution of this component stood at 1 .0 percentage point, down from its peak but still well above the 0 .5 percentage point that was typical before the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Because of the way the price index measures average rents for all tenants, both new and existing tenants, the changes in this segment of PCE price index are more subdued and tend to lag changes that are actually occurring in rents. As a result, says the Report, “this lag implies that measure of rent growth for new leases can help predict future changes in the PCE price index for housing services.” Therefore, as you can see from the chart below, the real-world measures of rents, percent changes from a year earlier, from places like Zillow and CoreLogic, peaked in mid-2022 and have fallen sharply since then. However, the PCE price index for housing services only peaked last year and should have further to go, at least that’s what the Fed Report anticipates, “However, as long as market rents continue to increase moderately, PCE housing services inflation should gradually decline and eventually return to its pre-pandemic pace as well.”

Maybe the prominent placement of analysis suggesting some degree of confidence that the future path of a key component of PCE inflation measures is lower, is the sort of evidence that can be highlighted as the Fed focus evolves, from weighted to inflation, to evenly balanced, and then, on to more heavily weighted to the labor market.