Market Pulse: June 10, 2024

Lou Brien is a Strategist/Knowledge Manager at DRW and keeps an eye on the Fed and the economy in general. He likes to say that he looks behind the headlines to examine the finer points of the data in order to not only know where the economy is, but where it is going.

For several decades, until 1993, the Cleveland baseball team, the Indians back then, played their home games in a massive lake front ballpark called Cleveland Municipal Stadium. There were seats in the place to accommodate 70,000 fans, but so many seats weren’t necessary most days. That’s because Cleveland has not won a World Series championship since 1948 and the years between then and the time the team got a new park in which to play, were not very successful. The attendance at Indian home games was more often than not the lowest, or almost the lowest in the league. Several years the average crowd was less than 10,000 per game, and it looked more even more meager considering the size of the stadium, which, by the way, eventually became known as The Mistake by the Lake.

John Joseph Adams first drummed at an Indian’s game in August 1973. He didn’t just drum during the exciting bits of the game; he didn’t play some sort of rapid-fire-rhythm to get the fans to rise to a crescendo. No, Adams just beat his drum, like a metronome, throughout the game. Thump…thump…thump…from the opening pitch to the final out. Adams was a fixture at Indians for the better part of five decades; he is said to have missed only 37 home games in 47 years. Thump…thump…thump. (For those not familiar with the professional baseball schedule, the full season is 162 games and 81 of those is a home game. So, the drummer was present at almost four thousand games; thump, thump.)

Back in the day, when the old Municipal Stadium was the home park, fans were able to distance themselves from the drummer. Though you couldn’t hide from the sound of the drum, his thumping was audible everywhere in the nearly empty park, it was after all a cavernous echo chamber.

But having said that, Adams was a unique part of the Cleveland Indian game experience; no other team had a drummer. Maybe it can be said that the drumming was simultaneously irritating and comforting. In any case the team celebrated his consistent presence, they encouraged him to continue his attendance at the new ball park and even gave away a bobblehead figurine in his likeness. Adams’ attendance streak came to an end during the 2020 Covid lockdown and after that he couldn’t get to the games for health reasons. He passed away in January 2023.

I’ve said it before and I plan to say it again, often…thump…thump…thump…; I do not buy into the idea that the Establishment Survey’s depiction of Nonfarm Payrolls as a pillar of strength is indicative of the current condition of the labor market, especially when many/most other labor market indicators, if not weak, are weakening and cautionary.

Today’s case in point, and there will be more to come…thump…thump…thump…is the divergence of the Nonfarm Payrolls and the Household Survey’s Employed data.

The Establishment’s nonfarm payrolls (NFP) counts jobs by surveying about 130,000 businesses. As its name implies this survey does not count agriculture jobs and related industries.

The Households Survey checks in on 60,000 people. This survey counts employees, and it includes employment categories that are not counted in the Establishment report, not only the agriculture and related industry jobs, but also self-employed workers whose business are unincorporated.

If a person has three jobs, the NFP counts three jobs. In the Household survey an employee counts for one, no matter how many hats they wear. But the extra employment categories in the Household Survey means that it has always been the bigger number between the two surveys.

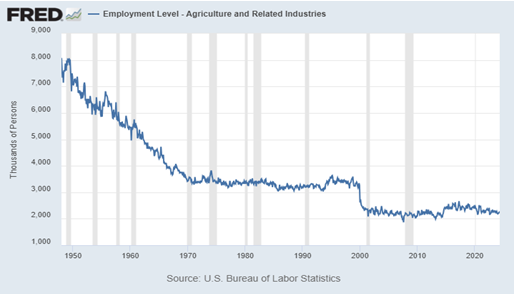

Back in the late 1940s there were about 8.5 million workers in agricultural and related industries. That number has shrunk by three quarters since then; as of May the total workers in Ag is 2.283 million.

So, it is no surprise that over the decades the spread between the NFP and the Employed has narrowed. But as you can see in the chart below the Ag jobs have stabilized in the general vicinity of the latest reading so that has not been a factor in the narrowing for a couple decades.

Seven decades ago, the Employed total was more than 14 million greater than the NFP. The decline in the spread over the years, most of it because of Ag employment, has been consistent, if not linear. But the recent action has been difficult to understand, even if you ignore the spike/recovery during the pandemic lockdown period in 2020.

In the last year the NFP has added 2.75 million jobs. The number of Employed also rose in the last year, but by just 376k. So, the spread between the two surveys has come-in by about 2.4 million. The spread was 4.920 million a year ago, it is 2.540 million as of May. Ag employment has fallen by 75k since last year, so this was not really a factor in the narrowing. Additionally, the Ag employee total at 2.283 million is now just 257k short of accounting for the entire difference between the two surveys, and that doesn’t make sense. One explanation, maybe the right answer, maybe not, is that one side of the spread between the NFP and Employed has been miscounted. I know what my guess is.

The Household survey also tracks the number of Unemployed people; the component that goes into the Unemployment Rate calculation. The number of Unemployed bottomed in December 2022 at 5.698 million; as of May 2024, the figure is at 6.649 million.

The increase in the number of Unemployed since the end of 2022 is 951k, not an insignificant amount. The Unemployment Rate hit a multi-decade low of 3.4% in January 2023, and hit it again a couple months later in April. The number of Unemployed had not yet begun to rise, but it has moved since.

The Unemployment Rate hit 4.0% in May; the first time that high since January 2022, it is up six tenths from the cycle low.

The previous three times the Unemployment Rate moved six or seven tenths off the low, the momentum was just beginning.