Market Pulse: June 24, 2024

Lou Brien is a Strategist/Knowledge Manager at DRW and keeps an eye on the Fed and the economy in general. He likes to say that he looks behind the headlines to examine the finer points of the data in order to not only know where the economy is, but where it is going.

As noted in this space in the first week of the year, 2024 is the biggest election year in history. That is true for the number of elections scheduled, but maybe also for the ramifications of the votes, although that is far from clear.

To be sure, it is a big year for the number of elections that are to be held. At the onset of the year The Atlantic Council figured there would be 83 national elections in 2024, to be held in 78 countries; and they noted the world will likely not see the same volume of elections again until 2048. The New York Times wrote that more than two billion people will have the chance to cast a ballot in their national elections this year in countries that combined account for about half the world’s population.

But it is also a big election year because of the potential changing of the guard/direction as a result of some of the voting outcomes. It certainly seems that there is a greater possibility now than at any time since the late sixties, that countries or regions will opt for the road not taken, and as opposed to less disruptive mid-course corrections.

Sure, most elections stick to the script. Mexico voted for a woman as President for the first time, but that was well foreshadowed, and no one can say the vote in Russia did not turn out as expected.

Some election results maintained the same pecking order for the political parties, but regardless can be seen as a reigning in of the current leadership; not so much a rebuke of those in power but more a reminder of political accountability. South Africa and India are examples of this.

For instance, Narendra Modi is still the Prime Minister of India after the national election in the world’s largest democracy but, for the first time during his decade in power, Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) no longer has an outright majority in Parliament. The change in the composition of the lawmakers was immediately noticeable, reports Bloomberg, “Signs of acrimony between the BJP-led government and the opposition were visible Monday (June 24) at the start of the first parliamentary session since election results earlier this month.”

In South Africa the ruling African National Congress (ANC) was denied its outright majority for the first time in three decades. From 1994, when Nelson Mandela led the ANC into power, until last month’s election, the party was able to rule as they saw fit, but not anymore; now results matter.

And so, the likelihood for Indian and South African politics in the short or medium term, that sliver of the future that is foreseeable, is either compromise or stalemate, but not metamorphosis or revolution.

But then there is France. There hasn’t been a national election so far this year in France and, for that matter, none was previously planned for 2024. But now the calendar shows us that France’s two-stage legislative election is scheduled for June 30 and July 7.

The election was a surprise. It is President Macron’s unexpected political gambit unveiled after his party got trounced in the EU Parliamentary election in early June. It can be said that the gist of the matter is not so much that Macron’s Renaissance Party did so poorly, but rather it is about the party that did so well in the European vote that pushed forward the French election.

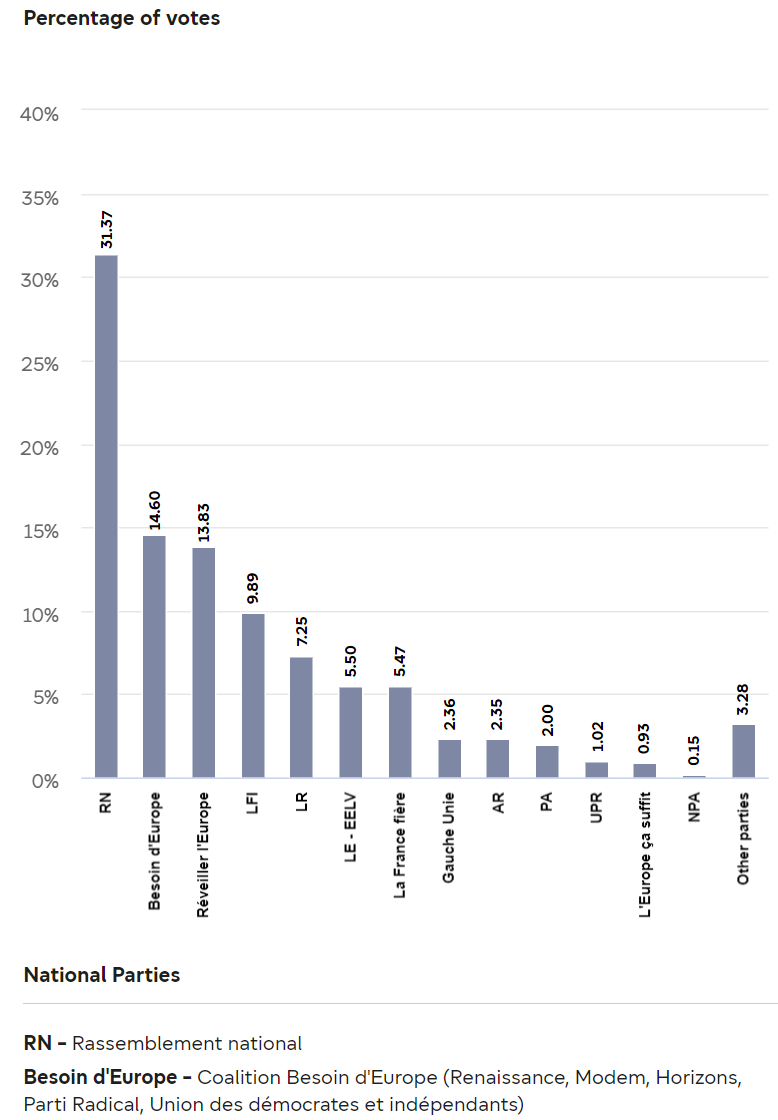

Rassemblement National (RN or National Rally) won the largest share of France’s representation in the EU Parliament. The RN took 31.37% of the French total, more than double the percentage of the seats won by the Besoin d’Europe coalition that includes Macron’s group.

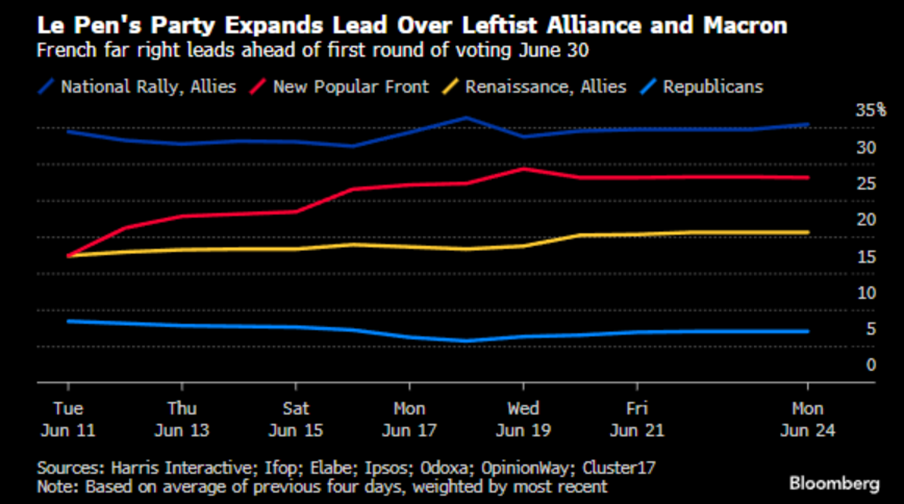

RN is of course the latest version of the xenophobic/anti-Semitic party founded by Jean Marie Le Pen in 1972, the National Front. Marine Le Pen has spent the last couple of years trying to erase the origin story and claim it is a new day for the National Rally; that’s the reason she changed the party’s name. Additionally, the future face of the party, Jordan Bardella, is only 28 years old, so he has plausible deniability about the past. Regardless, the RN has never before been in such a powerful or popular political position. Ms. Le Pen has steadily improved on her results in Presidential elections over the last decade, she won 41.45% of the vote in 2022. And now the party seems ready to build upon that and the recent EU results as well, in this Sunday’s election. A composite poll of polls assembled by Bloomberg shows RN with 35.4% of the vote for seats in the legislature, leading a new leftist alliance, the New Popular Front, by more than seven points; Macron’s coalition is third with 20.6%.

I’m not here to judge whether or not RN has changed its spots, but clearly Macron does not believe that to be the case. The French President spoke on a podcast recently, he said, “I think that the solutions given by the far-right are out of the question, because it is categorizing people in terms of their religion or origins and that is why it leads to division and to civil war.”

On the next two Sundays the voters will get to choose.

What is clear is that the center is not holding. It is obvious in France, as can be seen in the poll results above; the strength of the far-right and far-left and the weakness in the parties representing the status quo. The more distant and disparate the party distribution the more difficult it becomes to govern. Ask Germany.

The fractured results in the last German election resulted in a coalition of strange bedfellows; the Social Democrats leading the Free Democrats and the Greens. The support for this combination at the time they came together was 52%. But the ineffective group has seen its support decline by forty percent or more. On the other hand, the outer reaches of the German political spectrum the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) has surged, they finished second overall in the German seat allocation at the recent EU Parliamentary election. Also strong in that vote was the newly formed left-populist party, Bundnis Sahra Wagenknecht. There is no denying that the US is also living this political story. The center of the US political spectrum has long ago hung a “Vacancy” sign. Articles have been written about the exodus from the middle for three decades, but it is fair to suggest the chasm is as big as it has been in more than a half century. The November election will tell the tale, but the preamble begins with the Biden/Trump debate Thursday June 27.

In each instance – France, Germany and the US—the further afield the parties go, the more people are left behind, at least in the initial part of the game. Every political conflict consists of two parts: the actively engaged, such as the early adopters of the extreme parties, and the bystanders, the “audience that is irresistibly attracted to the scene,” as described by E. E. Schattschneider, in The Semisovereign People. “To understand any conflict it is necessary therefore to keep constantly in mind the relations between the combatants and the audience because the audience is likely to do the kinds of things that determine the outcome of the fight. This is true because the audience is overwhelming; it is never really neutral; the excitement of the conflict communicates itself to the crowd. This is the basis pattern of all politics. The first proposition is that the outcome of every conflict is determined by the extent to which the audience becomes involved in it…. …the balance of forces in any conflict is not a fixed equation until everyone is involved….

The moral of this is: If a fight starts, watch the crowd, because the crowd plays the decisive role.”